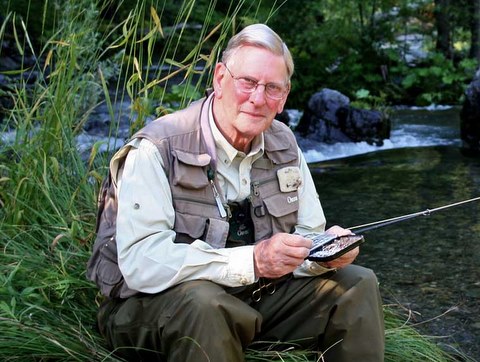

Peter Lapsley

1943 – 2013

Peter Lapsley’s funeral service took place at Mortlake Crematorium on 19 August 2013. His long-time friend and fellow angling writer Neil Patterson delivered the eulogy. Here is an edited version of his address. We are grateful to Neil for his permission to reproduce this tribute.

Just as you’re leaving Watford, heading North West to Hunton Bridge, there’s a left turn to Cassiobury Park that takes you past a mansion house called The Grange. This was once the home of Fanny and Johnny Craddock, the first TV chefs of any note.

Carry on until you get to a bridge over the Grand Union canal. Cross this. Take a right, and follow the footpath until you get to a lock. A stream runs into the canal on the other side.

Cross over the lock and plonk yourself at the end of a small concrete shelf and place your float and maggot just where the stream hits the canal.

This is where Peter caught his first roach, aged six.

How do I know this? Because, 10 years later, it’s the exact place where I was to catch my first roach, too.

Coincidences continued.

Peter and I went to the same prep school. Shirley House in Watford, now defunct. Peter was eight years older than me, so our paths never crossed.

Later I was to discover that we cast our very first dry flies on the very same chalkstream. The River Chess. Peter was 12. I was about the same age, too.

In fact I only got to meet Peter many years later – in the 70s. He was fishing my beat on the Wilderness stretch of the Kennet, as a guest of Ron Clark.

In the 80s Peter disappeared briefly to run his trout fishery at Rockbourne and we lost touch. I visited him there once – and was invited on the last day to ‘mop up the stockies’. But Peter and I were destined to meet up again, which we did. Again by coincidence.

There he was, standing next to me on the platform at West Kensington tube station. He’d sold Rockbourne and returned to the MOD as chief inspector of aviation security after Lockerbie. A job he didn’t enjoy. He developed a scheme compelling airports and airlines to self-inspect, but this inspectorate was reduced, him with it.

But at last we were neighbours and continued to be so to the end. We both moved around London a bit, but we were never more than fifteen minutes away from one another.

Peter was a great conversationalist and enjoyed nothing better than a good natter, though he talked little about his years at Sandhurst. Except he was proud to have been their best shot – and captain of the rifle shooting team.

He talked even less about his 10 years commissioned service in the King’s Own Royal Border Regiment in British Guyana, Aden and the Emirates. Lots of dry sand, but not much dry fly fishing to talk of there. Northern Ireland, he only talked about once.

Fishing, however, he did talk about.

They say you can tell the character of a man by the flies he ties. Peter was no exception. His flies were immaculate. Each material systematically and carefully selected. Each turn of silk cautiously calculated. Watching Peter tie a fly was like watching a nervous man eat a kipper.

And, of course he was a wondrous fly fisherman and fly caster.

His relaxed style was developed when he was at Rockbourne. Being a full-time fisheries manager, quote: “cured me of any wish to catch and kill fish”.

But Rockbourne lakes included a delightful stretch of chalk stream which allowed Peter to study the trout and their environment at close quarters and in great detail which led him to become more interested in imparting this huge knowledge and passion he’d acquired to others.

To do this properly (Peter liked to do things properly), he went on to pass all the necessary exams to become a nationally qualified game angling instructor.

For this reason, perhaps more than any other British writer in recent times, he helped beginners and seasoned fanatics understand their sport better, allowing them to improve and progress their development.

As a ‘fly-fishing database’, his ability to collect, codify, simplify, and cut away mystique – without once letting his ego or self-interest get in the way – was and is a rare quality amongst sports writers. Peter’s exacting, military background made him a master of this.

He was not a man that traded in the unnecessary. To drive him really crazy, you just had to tell him things like your Daddy-long-legs pattern just has to have six legs.

“Trout can’t count,” he’d tell you Richard Walker had once told him.

… Or that there’s a better imitation of the Black Gnat than the one everyone been using for years.

We fishermen are not getting any younger.

Catching our reflection in the river we’re reminded that we’re not the young tearaways we still think we are. (At least, not all of us.) We stoop. That hair’s disappeared. Our legs are bandy. We walk slowly. Some of us can’t even see our reflection clearly, but we toss all this aside, because 70 years isn’t old. It’s young. Which is why Peter’s death seems so cruel and unfair.

Yet, it wasn’t. To the end, Peter was the bravest of men. I truly lost count of the convoy of medical conditions that kept arriving between our weekly four o’clock tea and cake sessions.

Every time he went away, I worried about him. I had good reason. But off he’d go.

In Egypt, he fell off a pyramid. Not really, but this is how we shrugged it off. Looking back, this was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Or rather, Peter’s hip. The flood gates of medical misfortune seemed to open up after this.

They discovered he had osteoporosis. In Sri Lanka, he bent over to pick up his suitcase, and broke one of his vertebrae. Then the doctors finally discovered the root of all his problems:

Peter had systemic lupus, a name given to a collection of diseases where the immune system becomes hyperactive and attacks normal, healthy tissues: your joints, kidneys, blood cells, heart, lungs. Quite simply, it takes no prisoners.

But brave Peter was a trifle bemused to find out he was a very rare item indeed, as lupus is more commonly found in middle-aged black women!

Then on his last trip to France this July, he came back not well enough for our usual tea and cake session and went back to his doctors for a check-up. They discovered he had leukaemia.

Peter didn’t have to look up the British Medical Journal where he had been Patient Editor since 2005 to know what that meant. Or to find out about the horrific treatment that was to follow.

… And then, when all this was successfully completed, he would have to have his hips redone.

When I visited him at the Hammersmith Hospital two days before he died, he was resigned to the fact that this time he really wasn’t going to be able to fish again.

I’m happy I stayed very close to Peter. We fished, lunched, tea and caked together often. We holidayed together. Above all, Peter and I fished his beloved Derbyshire Wye together where he was at his happiest. Even though it meant sitting on a bench by Duffer’s Pool casting at whatever was nearby.

These precious hours we spent together gave me time to do something only a few, the very closest, could monitor.

As his good health slipped quietly and painfully away, I wasn’t watching a man in retreat. Or a man who displayed the tiniest iota of anger about the blows life had dealt him.

This is because he was a man fulfilled in so many ways. And here’s how I’d sum this up:

At last, in 2012, he was made a life member of a club he’d dedicated so much of his time to, The Flyfishers’ Club. A hugely supportive and enthusiastic Club and Committee member, he sponsored many new members – including myself.

As a highly dedicated and quietly relentless editor of the Flyfishers’ Journal which he took over in 2007 – the only person to have served a second period as sole editor – tirelessly he continued to ‘up’ the standard despite ill-health, right until his death.

The fly-tying classes he so successfully ran for The Club throughout the past two winters gave him great joy and satisfaction. Tying up each stage … of each fly … for each student so they knew exactly what was going on.

But his dedication is best demonstrated in the way he used his limited number of guest tickets on the Wye to take members of the class fishing there.

He was and is a literary giant. He was the first person Richard Walker asked to take over his angling column in one of the leading fishing magazines of the day. Dermot Wilson said of him: “Peter has two great gifts which I envy: he never wastes a word and every word is a mot juste”.

As well as his relentless number of magazine articles – sometimes under the pseudonym ‘Grey Duster’ so he could write for more than one at a time – he has to my knowledge now written, co-written or edited ten angling books, including the bestseller, Fly Fishing by J R Hartley.

Not forgetting, his comprehensive guide to fishing in the Falkland Islands, where his father had spent his youth, and where he had visited when he worked in aviation security

Rare for recent angling writers, most of his books have gone into second editions. His latest, A Pocket Guide to Matching the Hatch, which he wrote with Cyril Bennett MBE, is a typically uncomplicated, thoroughly useful, brilliantly straightforward book that pulls together all the great works done on the subject in a practical guide no larger than a fly-box.

Peter was always a lover of the Abbots Barton water on the Itchen where he was once a syndicate member and a supportive commentator through its more recent rocky history. But he spent some of his happiest days on the “pretty little” Meon, as a member of the Portsmouth Services Fly Fishing Association.

More recently, Peter found the river that was to fulfil all his dreams. The Cressbrook & Litton waters on the Derbyshire Wye where he became a member – and where he was loved, both by the members – and the owner of the inn where he stayed.

His photography had reached a high professional standard. When he couldn’t fish, he could still hire a buggy at Kew and go shooting birds , flowers and butterflies.

He had a 2,200 word monthly column that was essential reading for all in FlyFishing & FlyTying, a magazine he had contributed to for every edition since it was first published in the summer of 1990. Nearly a quarter of a century.

No other fly-fishing writer interviewed so many of the leading fly-fishing luminaries and commented so passionately and effectively on the issues of the day.

He had plans for another book. This time, simplifying ‘Pond Life’.

Finally, as well as helping and inspiring thousands of fly fishers who had never met him, he was able to help one of his dearest friends who had.

Peter never put himself first. And make no mistake; none of us was closer to John Goddard, or a more loyal friend.

From the day John was unable to drive himself to his fishing, Peter was there – almost every week for the last five years of John’s life – right up to the close of last season – making sure his friend fished until he could fish no more.

This meant driving from Ealing to Surrey to take John to his lake half an hour away. Or to Rochiene Pearce’s water on the Itchen at Fulling Mill in Hampshire. This meant leaving very early and getting home late.

At one time, I swear Peter was in not much better health than poor John.

But that was Peter. He never complained. He was John’s friend, to the end. Who’d have guessed that just seven months after John passed away, we’d all be here today?

Yes, Peter would tell you, he was a fulfilled man. He had everything but his health.

In the opening paragraph of the very last article he wrote, yet to be published, for FlyFishing & FlyTying, his ‘end of season round up’ article that he wrote every year “It’s confession time”, he writes. “I have not fished once this year and it is possible that I may not be able to do so next year, either. The coincidence of an assortment of medical conditions – osteoporosis, osteo-arthritis, systemic lupus and their various complications – has combined to make me largely house-bound. That is frustrating, but it is not a plea for sympathy.

I count myself extremely fortunate to have been able to enjoy almost 60 years of fly fishing and to have been able to hitch onto that great sport three other equally enjoyable pastimes – fly-tying, writing and photography. To lose just one of those four, hopefully temporarily, is irritating, but that is all it is.”

Read Theo Pike’s tribute to Peter Lapsley on the Wandle Piscators website